The theme this week is, it seems, woodland, history, and its secrets.

Last June saw the publication of Emily Tesh’s Silver in the Wood. I missed it until now, with the publication of its loose sequel, Drowned Country, and I’m not sure whether to be sorry I missed such a gem last year, or glad that I had the opportunity to read two gems back to back.

Silver in the Wood sets itself in the forest called Greenhollow. Its protagonist is Tobias Finch, a quiet, pragmatic sort of man. Bound to the wood, he does not dwell on the past, but tends with a profoundly practical insistence to such forest problems as arise: fairies, ghouls, murderously angry dryads. His only companions are his cat and Greenhollow’s non-murderous dryads, for to the world beyond the wood, he’s a figure out of folklore, Greenhollow’s wild man.

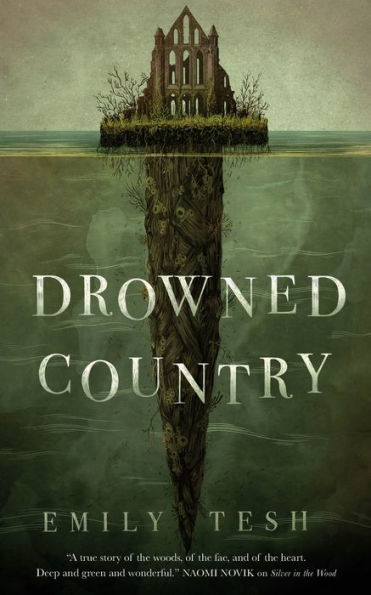

Buy the Book

Drowned Country

But when the handsome new owner of Greenhollow Hall, youthful folklorist Henry Silver, arrives in Tobias’s wood with endless curiosity and no notion that some secrets may be dangerous instead of wondrous, things change. Because Tobias, to his surprise, finds himself attached to Silver. And Silver is exactly the kind of man, come the spring equinox, to be the prey of the wood’s wicked, hungry Lord of Summer, who was once a man—but is a man no longer—that Tobias knew very well indeed.

Tesh has a deft ability to combine the numinous and the grounded: wildwood magic and the need to darn socks sit side by side. The arrival of the practical folklorist Adela Silver, Henry Silver’s mother, into the narrative gives Tesh’s world, and the characters of Tobias and Finch, additional dimensions, making already compelling people more complicated and interesting. The novella as a whole is gorgeously written, well-paced, and thematically interested in regeneration and regrowth as opposed to the stagnant, parasitic immortality of the Lord of Summer.

Drowned Country, its sequel, is part katabasis, part reconciliation, and part study in temptation, selfishness, the crushing weight of isolation and loneliness and hunger—

Perhaps hunger isn’t the right word, but it has the right weight.

Henry Silver has taken Tobias’s place. Bound to the wood—bound to where the wood once was, as well as where it is—and facing a kind of immortality, he is not dealing well with the new state of affairs. Especially since his own choices lost him Tobias’s regard. When his mother asks, however reluctantly, for his help, he steps out from the confines of Greenhollow to the damp, grimy seaside town of Rothport with its looming abbey and long-drowned forest: there to find a missing girl, a dead vampire, and a road to Fairyland in the drowned echoes of the long-lost wood.

And Tobias Finch, whom Henry loves, and who Henry believes despises him.

For such a slender volume, it carries a great deal of freight. Tesh’s combination of practicality and feyness is just as well-paired here, especially with Henry—a man with less talent for the practical than Tobias, and more inclination to be fey. Or to wallow in self-pity. Tesh mingles, too, humour and pathos, and a striking sense of narrative inevitability: the emotional and thematic climaxes have a very satisfying heft to them.

Well-recommended, these novellas.

Buy the Book

The Heirs of Locksley

The only fantastic element to Carrie Vaughn’s The Ghosts of Sherwood and The Heirs of Locksley is Robin Hood and all that ballad tradition mythos. But fantastically unlikely ahistoric historical personalities are a fine tradition in SFF and its adjacent works, and Vaughn gives us a version of Robin—for all that her novellas focus on his children—that feels grounded to a specific time and plausible in its outlines. The Ghosts of Sherwood sets itself immediately after the signing of the Magna Carta at Runnymede in 1215; The Heirs of Locksley, around the second coronation of the then thirteen-year-old Henry III at Westminster, four years after his first coronation at Gloucester. (Henry went on to have a relatively long life and reign.)

The language of these novellas reminds me of Vaughn’s striking, at times haunting, post-apocalyptic novels Bannerless and The Wild Dead (I dare not hope there’ll be other stories set in that world, because damn those are good): spare, plain, and perfectly sharpened to a point. Concerned with personal relationships, Vaughn’s pair of novellas are also interested in growth towards adulthood, and with living in the shadow of a story, or set of stories, that is larger than life: Mary, John, and Eleanor, the children of Robin of Locksley and his lady Marian, have to navigate a world that’s different from their parents’ youth, but one where the story of their parents’ lives, and the myths of Sherwood, and (some of) the antagonisms of the past, remain live concerns for them.

I enjoyed these novellas immensely. And not just because I’ve been brushing up on my medieval English history.

What are you guys reading lately?

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, was published in 2017 by Aqueduct Press. It was a finalist for the 2018 Locus Awards and was nominated for a 2018 Hugo Award in Best Related Work. Find her at her blog, or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council, the Transgender Equality Network Ireland, and the Abortion Rights Campaign.